Abstract

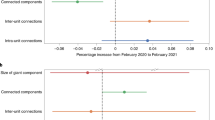

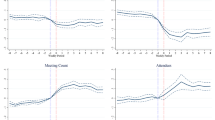

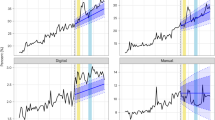

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused a rapid shift to full-time remote work for many information workers. Viewing this shift as a natural experiment in which some workers were already working remotely before the pandemic enables us to separate the effects of firm-wide remote work from other pandemic-related confounding factors. Here, we use rich data on the emails, calendars, instant messages, video/audio calls and workweek hours of 61,182 US Microsoft employees over the first six months of 2020 to estimate the causal effects of firm-wide remote work on collaboration and communication. Our results show that firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network of workers to become more static and siloed, with fewer bridges between disparate parts. Furthermore, there was a decrease in synchronous communication and an increase in asynchronous communication. Together, these effects may make it harder for employees to acquire and share new information across the network.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

An anonymized version of the data supporting this study is retained indefinitely for scientific and academic purposes. The data are not publicly available due to employee privacy and other legal restrictions. The data are available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission from Microsoft Corporation.

Code availability

The code supporting this study is retained indefinitely for scientific and academic purposes. The code is not publicly available due to employee privacy and other legal restrictions. The code is available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission from Microsoft Corporation.

Change history

05 October 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01228-z

References

Bloom, N. A. Working From Home and the Future of U.S. Economic Growth Under COVID (2020); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jtdFIZx3hyk

Brynjolfsson, E. et al. COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data. Technical Report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. 60 million fewer commuting hours per day: how Americans use time saved by working from home. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020); https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BFI_WP_2020132.pdf

Dingel, J. I. & Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 189, 104235 (2020).

Benveniste, A. These companies’ workers may never go back to the office. CNN (18 October 2020); https://cnn.it/3jIobzJ

McLean, R. These companies plan to make working from home the new normal. As in forever. CNN (25 June 2020); https://cnn.it/3ebJU27

Lund, S., Cheng, W.-L., André Dua, A. D. S., Robinson, O. & Sanghvi, S. What 800 executives envision for the postpandemic workforce. McKinsey Global Institute (23 September 2020); https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/what-800-executives-envision-for-the-postpandemic-workforce

Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380 (1973).

Burt, R. S. Structural holes and good ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 110, 349–399 (2004).

Reagans, R. & McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range. Admin. Sci. Q. 48, 240–267 (2003).

Uzzi, B. & Spiro, J. Collaboration and creativity: the small world problem. Am. J. Sociol. 111, 447–504 (2005).

Argote, L. & Ingram, P. Knowledge transfer: a basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. Process. 82, 150–169 (2000).

Hansen, M. T. The search-transfer problem: the role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Admin. Sci. Q. 44, 82–111 (1999).

Krackhardt, D. The strength of strong ties. in Networks in the Knowledge Economy (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

Levin, D. Z. & Cross, R. The strength of weak ties you can trust: the mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Manage. Sci. 50, 1477–1490 (2004).

McFadyen, M. A. & Cannella Jr, A. A. Social capital and knowledge creation: diminishing returns of the number and strength of exchange relationships. Acad. Manage. J. 47, 735–746 (2004).

Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. in Social Structure and Network Analysis 105–130 (Sage, 1982).

Burt, R. S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition (Harvard Univ. Press, 2009)

Baum, J. A., McEvily, B. & Rowley, T. J. Better with age? Tie longevity and the performance implications of bridging and closure. Organ. Sci. 23, 529–546 (2012).

Kneeland, M. K. Network Churn: A Theoretical and Empirical Consideration of a Dynamic Process on Performance. PhD thesis, New York University (2019).

Kumar, P. & Zaheer, A. Ego-network stability and innovation in alliances. Acad. Manage. J. 62, 691–716 (2019).

Burt, R. S. & Merluzzi, J. Network oscillation. Acad. Manage. Discov. 2, 368–391 (2016).

Soda, G. B., Mannucci, P. V. & Burt, R. Networks, creativity, and time: staying creative through brokerage and network rejuvenation. Acad. Manage. J. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.1209 (2021).

Zeng, A., Fan, Y., Di, Z., Wang, Y. & Havlin, S. Fresh teams are associated with original and multidisciplinary research. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01084-x (2021).

Levin, D. Z., Walter, J. & Murnighan, J. K. Dormant ties: the value of reconnecting. Organ. Sci. 22, 923–939 (2011).

Lengel, R. H. & Daft, R. L. An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship Between Media Richness and Managerial Information Processing. Technical Report (Texas A&M Univ. Department of Management, 1984).

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manage. Sci. 32, 554–571 (1986).

Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M. & Valacich, J. S. Media, tasks, and communication processes: a theory of media synchronicity. MIS Q. 32, 575–600 (2008).

Morris, M., Nadler, J., Kurtzberg, T. & Thompson, L. Schmooze or lose: social friction and lubrication in e-mail negotiations. Group Dyn. Theor. Res. Pract. 6, 89–100 (2002).

Pentland, A. The new science of building great teams. Harvard Bus. Rev. 90, 60–69 (2012).

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D. & Shockley, K. M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Int. 16, 40–68 (2015).

Ahuja, M. K. & Carley, K. M. Network structure in virtual organizations. Organ. Sci. 10, 741–757 (1999).

Ahuja, M. K., Galletta, D. F. & Carley, K. M. Individual centrality and performance in virtual R&D groups: an empirical study. Manage. Sci. 49, 21–38 (2003).

Suh, A., Shin, K.-s, Ahuja, M. & Kim, M. S. The influence of virtuality on social networks within and across work groups: a multilevel approach. J. Manage. Inform. Syst. 28, 351–386 (2011).

DeFilippis, E., Impink, S., Singell, M., Polzer, J. T. & Sadun, R. Collaborating During Coronavirus: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nature of Work. Working Paper 21-006 (Harvard Business School Organizational Behavior Unit, 2020).

Bernstein, E., Blunden, H., Brodsky, A., Sohn, W. & Waber, B. The implications of working without an office. Harvard Business Review (15 July 2020); https://hbr.org/2020/07/the-implications-of-working-without-an-office

Larson, J. et al. Dynamic silos: modularity in intra-organizational communication networks before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.00641 (2021).

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J. & Ying, Z. J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 130, 165–218 (2015).

Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C. & Larson, B. Z. Work-from-anywhere: the productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2020, 21199 (2020).

Kleinbaum, A. M., Stuart, T. & Tushman, M. Communication (and Coordination?) in a Modern, Complex Organization (Harvard Business School, 2008).

McEvily, B., Soda, G. & Tortoriello, M. More formally: rediscovering the missing link between formal organization and informal social structure. Acad. Manage. Ann. 8, 299–345 (2014).

Everett, M. G. & Borgatti, S. P. Unpacking Burt’s constraint measure. Social Netw. 62, 50–57 (2020).

Onnela, J.-P. et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 7332–7336 (2007).

Aral, S. & Van Alstyne, M. The diversity-bandwidth trade-off. Am. J. Sociol. 117, 90–171 (2011).

Brashears, M. E. & Quintane, E. The weakness of tie strength. Social Netw. 55, 104–115 (2018).

Burke, M. & Kraut, R. E. Growing closer on Facebook: changes in tie strength through social network site use. In Proc. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 4187–4196 (ACM, 2014); https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2556288.2557094

Herfindahl, O. C. Concentration in the Steel Industry. PhD thesis, Columbia University (1950).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Herbsleb, J. D. & Mockus, A. An empirical study of speed and communication in globally distributed software development. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 29, 481–494 (2003).

Ehrlich, K. & Cataldo, M. All-for-one and one-for-all? A multi-level analysis of communication patterns and individual performance in geographically distributed software development. In Proc. ACM 2012 Conf. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 945–954 (ACM, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1145/2145204.2145345

Cataldo, M. & Herbsleb, J. D. Communication networks in geographically distributed software development. In Proc. 2008 ACM Conf. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 579–588 (ACM, 2008).

Kolko, J. Remote job postings double during coronavirus and keep rising. Indeed Hiring Lab (16 March 2021); https://www.hiringlab.org/2021/03/16/remote-job-postings-double/

Ugander, J., Karrer, B., Backstrom, L. & Kleinberg, J. Graph cluster randomization: network exposure to multiple universes. In Proc. 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 329–337 (2013); https://doi.org/10.1145/2487575.2487695

Eckles, D., Karrer, B. & Ugander, J. Design and analysis of experiments in networks: reducing bias from interference. J. Causal Inference https://doi.org/10.1515/jci-2015-0021 (2016).

Bojinov, I., Simchi-Levi, D. & Zhao, J. Design and analysis of switchback experiments. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3684168 (2020).

Lechner, C., Frankenberger, K. & Floyd, S. W. Task contingencies in the curvilinear relationships between intergroup networks and initiative performance. Acad. Manage. J. 53, 865–889 (2010).

Chung, Y. & Jackson, S. E. The internal and external networks of knowledge-intensive teams: the role of task routineness. J. Manage. 39, 442–468 (2013).

Dennis, A. R., Wixom, B. H. & Vandenberg, R. J. Understanding fit and appropriation effects in group support systems via meta-analysis. MIS Q. 25, 167–193 (2001).

Fuller, R. M. & Dennis, A. R. Does fit matter? The impact of task-technology fit and appropriation on team performance in repeated tasks. Inform. Syst. Res. 20, 2–17 (2009).

Athey, S., Mobius, M. M. & Pál, J. The impact of aggregators on Internet news consumption. Preprint at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2897960 (2017).

Swisher, K. Physically together: here’s the internal Yahoo no-work-from-home memo for remote workers and maybe more. All Things (22 February 2013).

Simons, J. IBM, a pioneer of remote work, calls workers back to the office. Wall Street Journal (18 May 2017).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. Why working from home will stick. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020).

Bloom, N., Davis, S. J. & Zhestkova, Y. COVID-19 shifted patent applications toward technologies that support working from home. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020).

Workplace Analytics https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/workplace-analytics/use/metric-definitions (Microsoft, 2021).

Athey, S. & Imbens, G. W. Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-differences models. Econometrica 74, 431–497 (2006).

Iacus, S. M., King, G. & Porro, G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit. Anal. 20, 1–24 (2012).

Muscillo, A. A note on (matricial and fast) ways to compute Burt’s structural holes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.05114 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was a part of Microsoft’s New Future of Work Initiative. We thank D. Eckles for assistance; N. Baym for illuminating discussions regarding social capital; and the attendees of the Berkeley Haas MORS Macro Research Lunch and the organizers and attendees of the NYU Stern Future of Work seminar for their comments and feedback. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. analysed the data. L.Y., D.H., S.J. and S. Suri performed the research design, interpretation and writing. S. Sinha, J.W., C.J., N.S. and K.S. provided data access and expertise. B.H. and J.T. advised and sponsored the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.Y., S.J., S. Suri, S. Sinha, J.W., C.J., N.S., K.S., B.H. and J.T. are employees of and have a financial interest in Microsoft. D.H. was previously a Microsoft intern. All of the authors are listed as inventors on a pending patent application by Microsoft Corporation (16/942,375) related to this work.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Nick Bloom, Yvette Blount and Sandy Staples for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–21 and Supplementary Tables 1–25.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S. et al. The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat Hum Behav 6, 43–54 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4